Ink Drawing by Elijah Burgher

ESSAY

Magic: A Gramarye For Artists

First published in Documents Of Contemporary Art: Magic, Whitechapel Gallery and The MIT Press, 2021

If the excitable pronouncements of many contemporary art and culture magazines are anything to go by, we could be forgiven for believing that an occult renaissance occurs every couple of years. Articles declaring artists’ ‘rediscovery’ of witchcraft, or reengagement of magical thought, have encouraged a mood of inquiry in which respected curators, art historians, and academics host regular exhibitions and conferences on the resurgence of belief, pondering the recurrent magnetism of the numinous, often announcing, defining, and periodising the influence of the supernatural on the production of visual art.(1) These are spirited, enticing, and frequently fascinating celebrations, and they do help us to clarify the evolution of our relationship with the allure of the magical, of preternatural influences, heavenly correspondences, and the inexplicable. But according to this approach, our interest in esoteric themes – from animism, mysticism, and nature worship to herbalism, astrology, and alchemy – would appear to be nothing more than a simple reaction to spiritual or political deficits in the present.

The narrative of rediscovery is a compelling perspective, but it neglects the fact that these resurgences arise and subside so frequently that we may well ask whether this story is adequate to the representation, experience, or practice of magical modes of consciousness in the sphere of art making, let alone our spiritually complex post-secular lives in general. Indeed, it could lead us to wonder whether we have become spellbound by a superficial narrative of re-enchantment, a convenient tale we might tell ourselves to counter our own uneasy propensity for belief. What would it mean for us to accept the mysterious currents of magical intrigue that animate human cultures with the spirit of speculation as an unceasing continuum? What if we had never really been disenchanted?

As the philosopher Jason Ā. Josephson-Storm discusses in his book The Myth of Disenchantment: Magic, Modernity, and the Birth of the Human Sciences (2017), the monolithic telos of the modern, with its presumptions of scientific objectivity and rational thought, conveniently distorts the ways in which efforts to disenchant the modern subject have continually resulted in eruptions of belief and a renewed desire for spiritual sanctuary.(2) When James Frazer published his monumental (yet much contested) anthropology of magic, The Golden Bough, between 1890 and 1915, he imagined an evolutionary theory of magic based upon sympathies, contagions, and traces that connected the material and immaterial worlds, and that had its origins in the imagined fertility cults of antiquity. Despite Frazer’s secular social-scientific intentions, this catalysed a huge cultural response from romantically-inclined artists and writers dissatisfied with the dominant materialism of their present. Similarly, when Psychoanalysis postulated a science of the unconscious in the late 19th century, the spectre of the mind’s untapped capacity for telepathic interconnectedness would come to haunt Freud as an embarrassing, yet not entirely irrefutable, speculative excess (a history that both Susan Hiller and Jackie Wang touch upon in this collection). These historical oscillations lend themselves less to the story of a ‘dis’ or ‘re’ enchantment, than they do an awareness of the imminent co-production of the secular and the magical, a process that needn’t necessarily be perceived as reactionary, but as a broadening of our sense of just how weird the world actually is, and how limited any one interpretative approach might be for assessing its strangeness.

Heaven And Earth Magic, Harry Smith, Mystic Fire Video, 1957-62, 1989

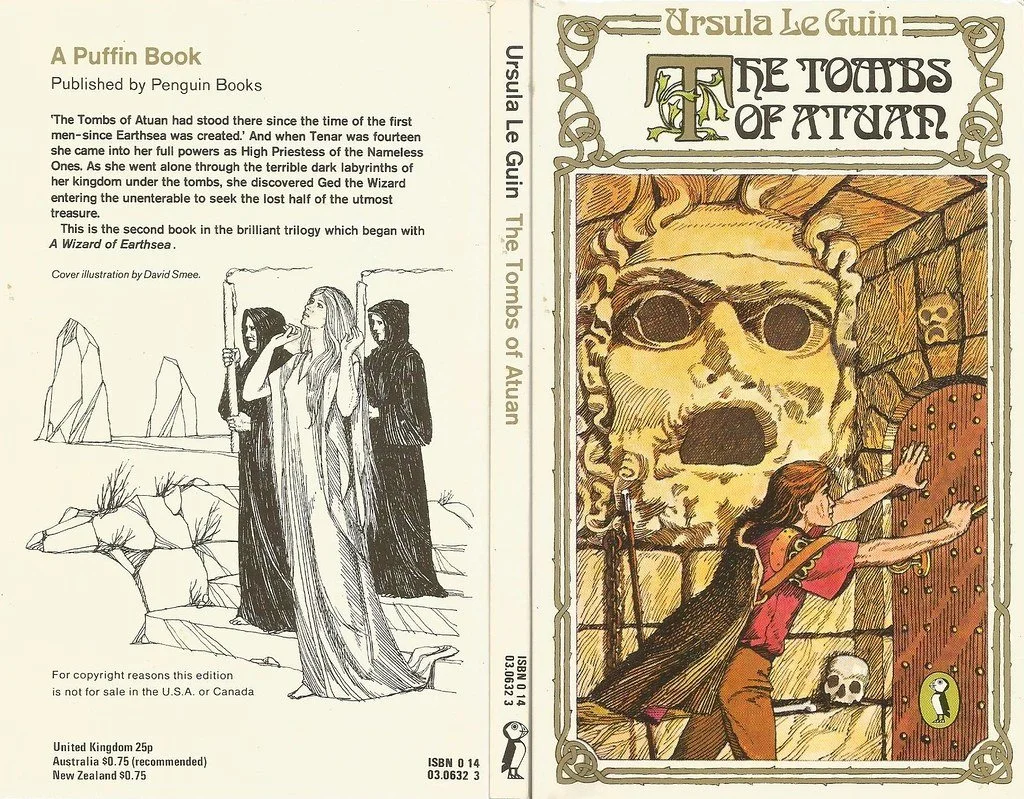

Magic has countless overlapping traditions, applications, and definitions, many of them remaining beyond public scrutiny. For the affluent initiates of early 20th ceremonial societies like The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, magic implied the cultivation of a spiritual discipline imparted by mysterious ‘Secret Chiefs’, and through which one might enter into conversation with a ‘Holy Guardian Angel’ that could bridge the void separating the phenomenal and noumenal domains.(3) For practitioners of the African American Conjuring tradition (explored in this volume by Yvonne P. Chireau), it could be a creative and spiritually resilient bricolage of indigenous botanical knowledge practices, traditional African and modern Christian spiritualities, that sought protection through techniques of ‘Hoodoo’. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s writers like Louis Pauwels and Jacques Bergier, and Colin Wilson, plied a great trade in pulp occultism, describing the untapped magical potential of the human animal as a dormant ‘sixth sense’ or ‘faculty x’ that could reconnect us to the realm of the unseen, a place where the paranormal bestiary of ghosts, cryptids, and UFOs might appear to us in sharper focus.(4) In literature, Ursula K. Le Guin would stress magic’s fundamental relationship to language through her popular Earthsea stories (1964–2001), where wizards sought to discover the true names of things in order to exert power and influence over them, thus shaping their realities through the utterance of emotionally charged speech acts. More recently, and through a method that rejects magic’s reliance on rarefied grimoires and initiatory cults, Aidan Wachter has written of a distinctly unpretentious and ecologically responsive ‘dirt magic’ that engages a ‘vast living universe of spirit-beings, be they human, animal, wind, rain, rock,’(5) in moments of contemplative and healing togetherness.

But magic has also been caught up in the categorical violence of classificatory techniques of exclusion, a strategy of sexist, racist othering that establishes power relations conducive to dominance. The internecine history of European Christianity provides us with an important example of just how facile this othering can be, as the Protestant Reformation of the 16th century simply announced the discontinuation of miracles and reinterpreted the processes of transubstantiation characteristic of the Catholic Mass as a form of idolatry or magical heresy. Silvia Federici has written hauntingly of the weaponisation of witchcraft accusations against women in her important work Caliban and the Witch (2004), suggesting they were used to bolster the rise of agrarian capitalism in England throughout the 16th and 17th centuries. These were politically strategic persecutions. They abetted the privatisation of land and often coincided with the enclosure of the common lands in rural counties, as a paternalist manorial system that had once granted customary rights to widows, elderly people and the poor, gave way to a market-focused economy.

As Randall Styers notes in his contribution to this volume, magic has also proved an especially pernicious marker of cultural difference and social control, allowing for the propagation of European and American imperialisms founded on false precedents of rational superiority. For Styers, the assumed critical clarity of Eurocentric anthropological inquiry has allowed for the scholarly production of ‘primitive’ or ‘traditional’ cultures, categorical fictions that would justify the suppression of both non-Western and Euro-American proletarian ‘superstitions’ by colonial and governmental expansion. ‘A propensity to magic demonstrates an incapacity for responsible self-government’, suggests Styers, echoing the observations of Edward Said, ‘people prone to magic call out for enlightened control.’ Indeed, such processes suggest that imperial authority might cloak itself with its own forms of secularised magic, tactics of reality management that falsely delineate the boundaries of what worlds might be deemed possible.

The Tombs of Atuan, Ursula K. Le Guin, 1970

Artistic interest in magic’s diverse cultures has commonly mirrored their resistance to conservative, consensual realities, from the heteronormative strictures of monogamy to a rejection of human exceptionalism and the mechanised destruction of the environment. We’ve only to observe the residual and emergent flows of art practice throughout the 20th century to see how replete it is with counter-cultural mysticism, from the guided drawings of the spiritualists to the development of early abstraction by Theosophically influenced painters, the interest in automatism by the surrealists to the Gurdjieff-inspired writings of the Harlem Renaissance. Bodies of work by Hilma Af Klint, Georgiana Houghton, Maya Deren, Harry Smith, Ana Mendietta, Betye Saar, Mary Beth Edelman, Kenneth Anger, and Derek Jarman suggest century-spanning lineages whose charged provocations continue to lend vigour to the experimentations of many politically and spiritually oriented contemporary practices.

This volume of the Documents of Contemporary Art series seeks to address the current appeal of magic as it might present itself to anyone wishing to develop a critical art practice. It is, to some extent, unapologetically enchanted in its editorial approach, often sidestepping exterior definitions of magic in favour of developing a critical thinking that accepts its own embeddedness in the production of new myths, magics and useable fictions. It is also a book that heavily prioritises the writing of artists, and of artists’ texts. It’s my modest contention that artist’s writing and magical writing may have significant yet underexplored correlations, playing as they both often do with techniques of invocation, embodiment, didacticism, and the evocation and manipulation of the symbolic.

Magic’s relationship with art is deeply strange and symbiotic. We could even say that magical practice is inherently artful. The casting of a protective circle, the weaving of a corn dolly, the spread of a tarot deck, the deep lulls of trance and meditation. Magical cultures and sentiments depend on aspects of performance, craft, and visual projection, and they frequently accrue tangible residues, a clutter of worked ephemera that aids and assists the maintenance and transmission of magical intent. When the magician draws a talisman to channel a desire into a charged image (as Austin Osman Spare demonstrates in this volume), they aim for a sense of ‘rightness’, a point of resonance in which the image feels appropriate to their aims. But despite the production of images and artefacts, magical cultures rely on a kind of discretion that seems alien to the hyper-visuality of contemporary art. Where magic has, for the sake of its own modesty, potency, and the safety of its practitioners, dwelt in the shadows, contemporary art frequently strives for recognition in a marketplace of frayed attentions. Irrefutably, magical cultures persist regardless of whether contemporary artists take an interest in them. From the solitary practitioners of hedge witchery to the ‘sky clad’ groupings of established Gardnerian covens, rambling New Age healers to the warring factions of long-standing occult societies, magic lives as a plurality of thriving spiritual ‘occultures’. These strains of magical practice provide rich repositories of learning. But they also offer examples and warnings of magic’s social composition—the novel ways it can catalyse the formation of groups and collectives, either embracing or challenging hierarchy, emerging into public focus or retreating into obscurity—and how the promise of secret knowledge can assist the deceptions of false gurus and create opportunities for cultic exploitation.

Stone Alignments / Solstice Cairns, Michelle Stuart, 1979

On first consideration then, magic and art may seem diametrically opposed, operating within differing regimes of visuality that prioritise contrasting techniques of occlusion or recognition. But as this book hopes to illustrate, art and magic may inform each other in novel and strategic ways in the production and negotiation of their own apparentness.

Discussing the structure of witches’ covens in the early 1970s, Cecil Williamson, Neopagan Warlock and founder of the British Secret Intelligence Service’s wartime ‘Witchcraft Research Centre’, compared the strategies of discretion used by modern covens to those of surveillance agents and intelligence cells.(6) Such techniques of social evasion might find echoes in the tactics of contemporary art-adjacent political action, for example in the community-based reality-testing activism of the Center for Tactical Magic (interviewed by Gregory Sholette in this book); the exploration of queer sensualities in Elijah Burgher’s ‘Gay Death Cult’ (described by Alan Doyle, also in this volume), or more recently; Cassie Thornton’s proposal of ‘The Hologram’ as a feminist, peer-to-peer model of physical and mental healthcare provision that addresses the scarcity of treatment in a post-crash, post-pandemic moment.(7) In these instances, activism borrows magical tactics of communal discretion to offer paradigm-challenging alternative social assemblages.

Magic is mythopoetic, it sustains itself on the active creation of inhabitable myths. In this regard, it poses an ontological quandary to the subject of fiction. As Susan Johnston Graf notes in her book Talking To The Gods (2015), various members of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn used their artistry as writers to create works of visionary poetry and prose that could work as didactic tools. Authors like W.B Yeats and Dion Fortune redirected their magical ideas of animate life-worlds and psychical-ethers into the minds and bodies of a broad, curious readership who would metabolise their messages in unpredictable ways. The founder of modern witchcraft, Gerald Gardner, would even employ fiction in the form of his novel High Magic’s Aid (1949) to relay the syncretic teachings of Wicca, the ‘craft of the wise’, to the public without suffering the legal repercussions of the Witchcraft Act which had been an active part of British legislation since 1735.(8) In recent years, comic book authors such as Grant Morrison and Alan Moore (who appears as a contributor in this book) have radically expanded the confines of their medium into magical narrative systems that test the act of writing itself as a powerful tool of ‘hyper-sigilisation’ or gnosis.

Magic both informs and draws upon genres of critical, fantastical writing, but its influence has often tended to exceed the boundaries of literary form. Like its literary cousin Science Fiction, we might think of magic as a tool of defamiliarisation.(9) Unlike Science Fiction however, whose fantastical imaginings and speculative quandaries occupy a more cerebral mode of projection, magic works inwardly. Its postulations affect us on the more immediate and tangible level of felt experience, of belief, desire and embodied being. Where Science Fiction directs our attention to the matrices of social and technological change, magic works to challenge our perceptual and emotional bases for engaging the world, it encourages us to think metaphorically and associatively (as Gary Lachman suggests in his essay ‘Rejected Knowledge’), to look for resonances and points of synchronicity. We might think of this as a kind of willed madness, a productively destabilising chaos that magician Phil Hine reflects poignantly upon in this book when detailing his own experiments with the tentacular dreamworlds of H.P. Lovecraft and all of their nightmarish non-human denizens. Thinking beyond the immediate remit of this publication however, we might also question magical culture’s reliance upon the literature of the fantastic, and heed Ebony Elizabeth Thomas’s observation that the techniques of escapism promised by fantastical literary traditions are rarely free of the strictures of racial systematization that plague the lived world; tropes that are perhaps best engaged through the lens of a critical race theory.

Modern Paganisms promise a reconnection with nature, but we would do well to question this idea of the natural as a simple, redemptive and uncluttered catalyst of religious holism. As anthropologist Amy Hale has noted, there is a distinctly colonial residue within contemporary Pagan figurations of the environment as sacred places of connection with unseen energies and benevolent deities.(10) In contexts like the United States, white cultures of nature worship are practised on lands that have been violently and irrefutably expropriated from indigenous communities. In their essay, ‘White Magic’, included in this collection, Lou Cornum reinvokes the absent subjects of these appropriated spiritualities and their relationship to the land, prompting a vital questioning of what forms of cultural and bodily erasure underscore the practice of contemporary magical belief.

It is my hope that the materials gathered in the first chapter of this book prompt a kind of ‘magical-critical’ thinking that retains a sense of magic’s wonder while allowing us to reflect on the complex circumstances that underscore its production and practice. Magic possesses its own forms of criticality, and we needn’t always import the critical as an additional device to lend reflexive value to it. While ‘magical thinking’ is a term that commonly implies delusion, these texts propose various approaches to ‘thinking magically’ as a form of politically engaged and aesthetically tempered investigation. The chapter begins with the expansive words of Charles Fort, whose heady assemblage of unexplained phenomena The Book of the Damned (1919) acted as a lay-philosophical riposte to the constrictions of scientific arrogance in the early 20th century. For Fort, every science was a ‘mutilated octopus’, whose ‘clipped stumps’ disallowed it from feeling its way into ‘disturbing contacts’. Where scientific method prioritises lab testing and replicable results, Fort stressed the importance of the anomalous, the irregular, and the aberrant. The writers that follow him offer analytical tools shaped by the possibilities of the otherworldly. For Lucy Lippard writing in 1974, artists looking back to the mythical domain of prehistory were seeking to evade the patriarchal colonisation of the art historical canon, finding animist energies of connectivity in the hazy recesses of fortuitously ill-defined archaeological histories. Louis Chude Sokei redefines the ‘big bang’ as an occulted listening practice attuned to the tonal resonances of diasporic sound, while philosopher of science Isabelle Stengers ‘smells the smoke of the burned witches’ as a visceral provocation to rethink the exclusionary parameters of scientific discourse and situated knowledge practices. Simon O’ Sullivan offers five reflections on the hybridisation of art and anthropology that constitute novel forms of ‘fictioning’, proposing a sensitivity to the imaginary that the writer and fortean Mark Pilkington extends to the possibility of the ‘imaginal’ – a weird zone of anomalous experience that requires careful articulation in its artistic, cultural, and even psychiatric responses.

Chapter two traverses the occluded byways of a ‘Shadow Modern’, tentatively mapping the dimly-lit substrata of mystically-inclined artistic practices that have remained less visible to art history. Rather than producing a straight chronology, this chapter offers a litany of intergenerational correspondences, sounding the recursive echoes of magical culture throughout the 20th century and into the 21st, moving between visionary texts of the theosophists, through spiritualism, surrealism, and reflections on land art. AE was the pseudonym of George William Russell, an Irish writer and painter whose transcendent perceptions fed into a politicised Celtic Mysticism that channelled the voices of spectral comrades into a confrontation with the British colonial occupation of Ireland. Anna Zett reflects upon their secular use of a handmade Tarot deck to summon a difficult German modernity into the present, working through personal and historical dynamics of resistance. In this chapter you’ll find irksome ectoplasmic eruptions, hermaphroditic cosmologies, pagan anti-nuclear protests, conceptual kabbalah, and séance-like ventriloquisms in texts by Holly Pester, Ithell Colquhoun, Monica Sjöo, Jack Burnham, Jeremy Millar and Katrina Palmer respectively, writings that suggest an alternative understanding of the modern as a non-linear entity, a cacophony of transhistorical echoes.

Sticky Zeitgeist: Episode 2, Porpentine Charity Heartscape, check it out at https://porpentine.itch.io/

The third chapter looks to magic’s complex relationship with technology in an exploration of Ritual Media. Drawing upon Erik Davis’s conceptual archaeology of the magical-metaphorical precedents that continue to influence our understanding and development of new technologies, this chapter questions the intrusion of the magical into artists’ engagement with the digital via Mark Dery’s sober riposte to technopaganism, and reintroduces the essence of the divine into early explorations of cyberfeminism through Elaine Graham’s fusion of the thought of Donna Haraway and Luce Irigary. While Alice Bucknell announces the emergence of the ‘new mystics’, drawing upon the work of Zadie Xa, Haroon Mirza, Tabita Rezaire and others, Gary Zhexi Zhang channels the disquieting voice of the more-than-human through the interdimensionally receptive artworks of Jenna Sutela. In a chilling text written especially for this book, artist David Steans ‘legend trips’ an apparent curse surrounding a children’s television show of dubious authenticity, while game designer Porpentine Charity Heartscape tests the erotic depths of The Legend Of Zelda through an arresting excercise in hyper-sensual fan fiction.

Finally, deriving its name from a popular self-help manual published in 1930 by Dion Fortune, chapter four, Psychic Self Defence, looks to the use of magic as a tool of emotional resilience, community formation, and oppositional organizing. Finding solace in the quasi-spell form, Diane Di Prima, Linda Stupart, Joy KMT and Sean Bonney offer potent retorts to misogynist violence, the continued trauma of racism, and the malaise of a capitalist realism. Allan Doyle and artist Caspar Heinemann tap mysticism for forms of queer communality, while Jackie Wang reengages Freud’s notion of ‘oceanic feeling’ – a psychoanalytic term for feelings of immensity and interconnectivity – from a communising perspective, accounting for ‘feelings-in-common’ that might suggest new ways, and even worlds, of being together.

We might ask what use an interest in magic is when our current political reality appears to be sculpted by the machinations of dark magicians operating in the halls of power. As Gary Lachman and Benjamin R. Teitelbaum have recently demonstrated, currents of both US and Russian political culture have been influenced by occult thought in very real ways, with former American presidential aide Steve Bannon and Putin advisor Aleksandr Dugin both citing the writings of esoteric traditionalists in their policy making, reactionary decisions that have shaped the immediate character of our geopolitical terrain.(11) Magic’s political orientation is disquietingly malleable, and its popular embrace has tended to find purchase in fascist milieus as often as it has progressive orientations. As faith in political representation has subsided, new zones of superstition have emerged in which the supposed surety of dangerous counternarratives has taken root. We can’t assume that magic’s techniques of reality manipulation – whether viewed in a secular sense as a form of tricksterism or misdirection, or in a literal occult sense – are free from contemporary political misuse, or that they remain the preserve of a left, liberal counterculture. Where the Yippies(12) of the late 1960s once attempted to levitate the Pentagon in protest at the ongoing war in Vietnam, the new-born mystics of 4chan and 8chan have recently engaged a nihilistic numerology as a tool of populist ‘wish-fulfilment’, while the disorientations of a ‘post-truth’ era have allowed the projections of groups like Qanon to resolve themselves into electorally destabilising ‘conspiritualities’.

‘Post-truth’ itself carries the magical charge of a willed blurring and reshaping of reality affected by a stubborn application of intent to language. Such realisations don’t discredit an interest in magic’s potential use for progressive purposes (as a majority of the writings gathered here demonstrate), but they do suggest that its engagement needs to be cautious, sagacious, and self-aware.(13) More broadly, they imply that something akin to a ‘magical literacy’ that takes stock of magic’s historical and cultural persistence, might be one necessary mechanism amongst many for analysing the warped realities of our conspiracy prone present. Magic doesn’t replace the need for direct political action. The theatrical hexing of presidents might mobilise a public sentiment of distrust, but the resonances of such gestures can only find real traction in the spirit of popular resistance and organisation. This book hopes to provide a magical-critical lexicon for artists as we move forward into an inevitably weird and tumultuous future – a grammarye, or ‘magical grammar’, for strange times.

Notes

1. For instances of this narrative, see Suzi Gablik, The Re-Enchantment of Art (London: Thames & Hudson, 1991), James Elkins and David Morgan (eds.), Re-Enchantment (Abingdon: Routledge, 2009), Tom Jeffreys, ‘The Return of the Witch in Contemporary Culture’, frieze (26 November, 2018) (https://www.frieze.com/article/return-witch-contemporary-culture).

2. Joseph Ā. Josephson-Storm, The Myth of Disenchantment: Magic, Modernity, and the Birth of the Human Sciences (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2017) 125–152, 199–203.

3. See Francis King, Modern Ritual Magic (New York: Prism Press, 1970/1989), Rodney Orpheus, Abrahadabra: Understanding Aleister Crowley’s Thelemic Magick, (San Francisco: Weiser Books, 2005).

4. See Louis Pauwels and Jacques Bergier, The Morning of the Magicians, (St. Albans: Mayflower, 1973), and Colin Wilson, The Occult, (London, Glasgow, Toronto, Sydney and Auckland: Grafton 1979).

5. Aidan Wachter, Six Ways: Approaches & Entries for Practical Magic (New Mexico: Red Temple Press, 2018) 21.

6. This quote appears in the charming, if slightly stilted, 1970 BBC documentary The Power of the Witch: Real or Imaginary? directed by Michael Bakewell, but readers may wish to pursue further information in Steve Patterson, Cecil Williamson’s Book of Witchcraft: A Grimoire of the Museum of Witchcraft, (London: Troy Books, 2014) 127–131, 227–230.

7. See Cassie Thornton, The Hologram: Feminist, Peer-To-Peer Health for a Post-Pandemic Future, (London: Pluto Press, 2020).

8. Philip Heselton, Gerald Gardner and the Cauldron of Inspiration: An Investigation Into the Sources Of Gardenerian Witchcraft, (Somerset: Capall Bann Publishing, 2003), 215–249.

9. See the chapter on Cognitive Estrangement in Dan Byrne-Smith (ed.), Documents Of Contemporary Art: Science Fiction, (London: Whitechapel, 2020) 22–97.

10. Amy Hale in conversation with Christina Oakley Harrington, The Treadwells Podcast, 4 May 2020 (https://www.treadwells-london.com/treadwellspodcast/episode/c0996173/amy-hale-1-of-2)

11. See Gary Lachman, Dark Star Rising: Magick And Power In The Age Of Trump, (New York: Tarcher Perigee, 2018) and Benjamin R. Teitelbaum, War for Eternity: The Return of Traditionalism And The Rise Of The Populist Right (London: Allen Lane, 2020).

12. ‘Yippies’ was the collective moniker of The Youth International Party. See Stewart Home, The Assault on Culture: Utopian Currents From Lettrisme to Class War, (London: AK Press, 1991) 67–8.

13. ‘The Pagan and Occult Fascist Connection and How to Fix It’, Amy Hale, Medium, 5 August 2019 (accessed at: https://medium.com/@amyhale93/the-pagan-and-occult-fascist-connection-and-how-to-fix-it-d338c32ee4e6).